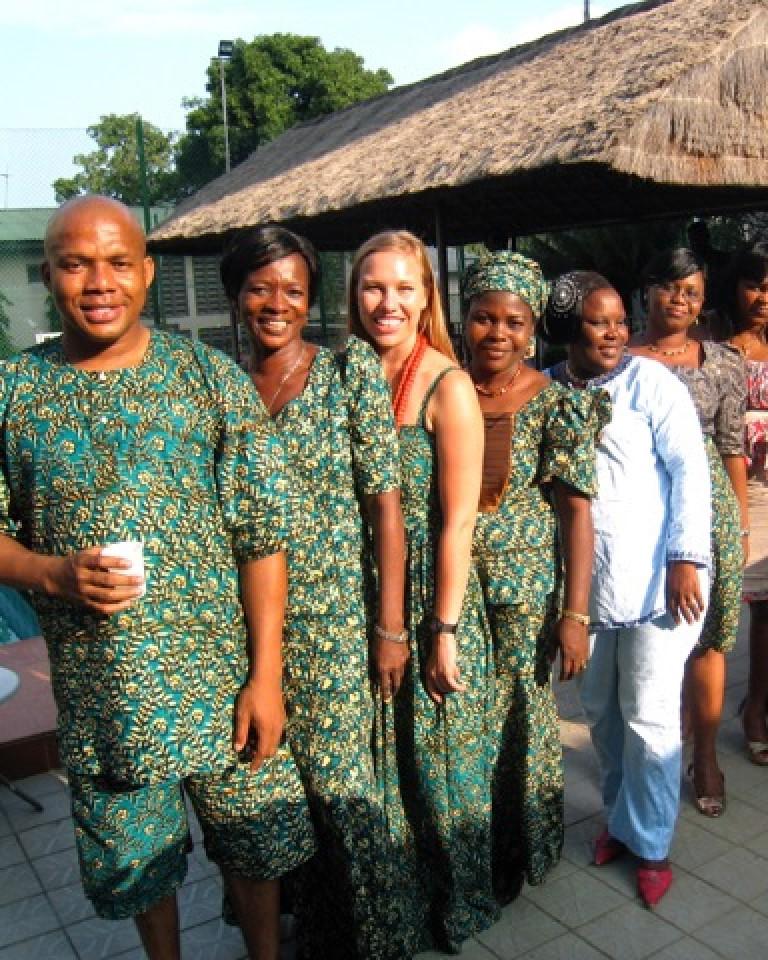

Stacey Vanderhurst

MENTOR SPOTLIGHT | MAY 2017

Department: Women, Gender & Sexuality Studies

Describe your work in a few sentences that we can all understand: I study how gender and sexuality impact migration politics in Africa and around the world. Right now, I’m writing a book about human trafficking interventions in Nigeria, where I have conducted research for almost ten years. I spent over a year doing fieldwork inside a shelter for human trafficking victims there, and what I found is that most women at the shelter didn’t see themselves as victims at all. My book uses stories from inside anti-trafficking programs to analyze that discrepancy between what women wanted in trying to migrate and what their government wanted in trying to stop them.

Q: How did you first get interested in doing research?

A: I studied abroad in Dublin when I was an undergraduate student, and living in a new social context really sparked my curiosity about social worlds. I grew up in a California agricultural community with lots of migrant farmworkers, but that just felt normal. Unlike rural California, Ireland has a national history of emigration. Immigration, on the other hand, was considered new to the country. These juxtapositions helped me look at these issues with new eyes, and I found great mentors to help me harness that curiosity into a research project about Nigerian asylum seekers. I applied for grants from my college to fund a summer of fieldwork for my senior honors thesis. Since then, I’ve never looked back!

Q: What do students in your discipline learn by doing research that they wouldn’t learn by just taking classes?

A: When you do original qualitative, ethnographic research, especially in gender and sexuality studies, you learn quickly that knowledge isn’t something that gets handed down to us in some perfect or pure form. Feminist scholarship emphasizes the collaborative nature of research, which requires you to sometimes set aside your own objectives and really listen to the people you’re trying to study. Our questions are constantly evolving, and with them the answers that might be most useful. This can be a very, very, messy and humbling process, but it ultimately provides the best foundation for transformative understanding of social problems.

Q: What do you find to be the most exciting part of doing research or creative work? What makes this line of work meaningful and interesting to you?

A: For me, the most exciting part of doing research is when I realize that I absolutely do not understand something. Usually this happens in really small ways. I’ll be talking to someone and suddenly she says or does something that makes no sense to me at all. That’s when I know I’m about to figure something out that I had never even considered. Getting to ask follow up questions – to sometimes spend months asking follow up questions – is the difference between just interesting conversations, and conversations for research. When I’m working with the right person, we get to go way deeper in our discussions than we ever would under normal social circumstances.

Q: What advice do you have for undergraduates interested in doing research in your field?

A: You definitely don’t have to move across oceans to look at the world with new eyes. My advice for undergraduates is to stay alert to all those little moments of bewilderment in your own lives and to feed your curiosity when they pop up. There are lots of chances in coursework, in campus groups, and in research-specific programs at CUR for you to pursue them further, but first you have to start purposefully holding onto that spark. The longer you wait to write it down or think it out, the more likely that your new insight will flicker away into however you understood things before. This combination of imagination and initiative is what makes researchers effective at any stage.

Q: For many students, doing research or a larger creative project is the first time they have done work that routinely involves setbacks and the need to troubleshoot problems. Can you tell us about a time that your research didn’t go as expected? Or about any tricks or habits that you’ve developed to help you stay resilient in the face of obstacles?

A: When I’m interviewing a group of women, like the women at the shelter, I purposefully let them direct a lot of our conversations. Sometimes I take the lead, though, and they still just talk about something else. This is frustrating, but also useful, because it means my questions aren’t resonating with their reality. For example, at the shelter, when I asked women how they thought about the danger of crossing the desert and ocean to get to Europe, they often changed the topic to something about God. To be honest, I’m not a very religious person, and often felt uncomfortable or even bored in these conversations. But when I took them more seriously, I realized that my framework for thinking about risk and reward did not work for how these women were making decisions. It took a lot of failure to learn that. The only caveat to that is that sometimes you have to allow yourself way more time than you think you should need. If you rush through your research, you may not have the chance to see things new ways.

Q: How do you spend your time outside of work?

A: I spend a lot of time outside of work doing what I also love in my work: connecting with friends, trying new things, and building community. Here at KU, that means I signed up for basketball season tickets before I even got to campus. Rock chalk!